There are two major types of ankle equinus: functioncal (muscular) or structural (osseous).

As per most foot pathologies, there are many possible causes for ankle equinus. The possible causes of ankle equinus are the following:

- Congenital gastrocnemius shortening

- Congenital ankle morphology deformity

- Acquired calf muscle shortness (tight gastrocnemius and soleus)

- Muscular imbalance

- Arthridities such as osteoarthritis or gout

- Neuromuscular imbalance or disorder (post-stroke for example)

- Leg length discrepancy: the shorter limb will plantarflex at the ankle causing equinus

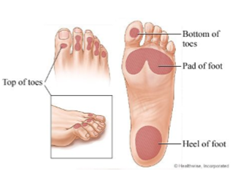

Depending on the amount of compensation available in the other joints surrounding the ankle, the equinus deformity leads to different types of problems. If you are dealing with an uncompensated ankle equinus, there is not enough motion in the ankle and surrounding joints for the heel to attain ground contact when you walk. This means your ankle would work in a plantarflexed position and most of the plantar pressures will be focused on your forefoot since your heel will not reach the ground, causing forefoot pathologies. When you apply more forces on your forefoot, this creates an increase in plantar pressure in the are which predisposes the patient to callus, foot ulcers, neuromas and metatarsalgia.

In a 2017 systematic review on diabetic foot ulcers, ankle equinus, and thus an increase in plantar pressures, were found in all studies where the patients involved had a history of foot ulcerations. This is why routine screening for ankle equinus in the diabetic population is crucial since it would allow the early onset of conservative treatment options to help reduce the plantar pressures and as a result, reduce the risk of ulceration (Searle, A., Spink, M., Ho, A., & Chuter, V., 2017).

If you are dealing with a fully compensated ankle equinus, there is sufficient range of motion in the surrounding joints such as the midtarsal joint and subtalar joint to allow the heel to attain the ground when you walk. The calcaneo-cuboid joint will pronate and the talo-navicular joint will supinate for the entire foot to make contact with the ground creating a rocker-bottom foot deformity. This results in biomechanical abnormalities including but not limited to overpronation, hypermobility in the midfoot and mobile pes planus pathology.

How do we measure ankle equinus?

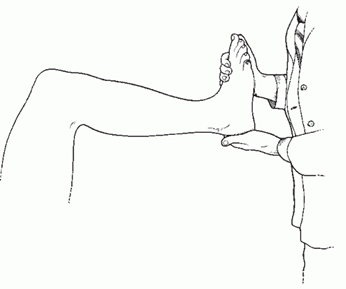

- Silfverskiöld test: The measurement of the angle between the lateral aspect of the leg and the lateral aspect of the foot with a goniometer. You perform this test with the patient sitting with the knee extended and then compare it with the results when the patient has their knee flexed. If there is an increase in ankle dorsiflexion with the knee flexed as opposed to with the knee extended, we know the equinus is due to a tight gastrocnemius muscle.

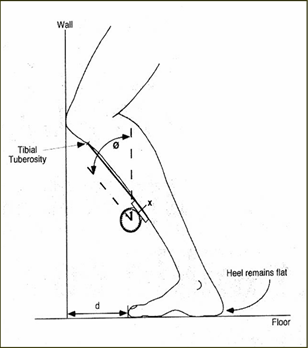

- Weightbearing lunge test: the patient faces a wall with their foot pointed straight forward and their knee flexing forward until it contacts the wall while making sure their heel remains on the ground. The patient places the measured ankle as far away from the wall as he/she can until the heel can no longer remain in contact with the ground. Then, the practitioner measures the distance between the wall and the longest toe with an inclinometer or with a goniometer between the fibula and the weightbearing surface. The normal distance between the wall and the longest toe is 9-10cm, but this varies depending on the patient’s height and the length of their limb (Clifford, C., 2014).

Ankle equinus can manifest as followed:

- Early heel lift if partially compensated. Ever notice people that look like they walk on their tippy toes when they walk like they are bouncing? That is because they have ankle equinus.

- Arch drops from non-weightbearing to weightbearing

- Metatarsalgia: pain in the ball of the foot

- Hallux abducto-valgus, hallux limitus

- Lesser toe deformities: hammer toes, claw toes

- Callus or ulcers in the areas with increased plantar pressures (forefoot for the uncompensated ankle equinus)

- Heel pain

- Shin splints

- Abducted angle of gait (feet point outwards when you walk)

- Increased knee flexion or hip flexion during the swing phase of gait to clear the ground (to not drag your feet from one step to the next)

Like always, the treatment depends entirely on the cause of the ankle equinus. Below is a list of possible treatment options for ankle equinus:

- Calf stretches (see Work it Wednesday posts on our Instagram page for examples of good calf stretches)

- Night splints: device that dorsiflexes your ankles and keeps them in a flexed position while you sleep to stretch the muscles

- Serial casting, usually when treated at a young age

- If you have a leg length discrepancy, lift therapy will help reduce the supination of the shorter leg

- If you are dealing with an osseous equinus due to congenital ankle morphology or a type of arthritis, a heel lift insert is recommended inside your shoes

- Custom foot orthotics to control the midtarsal joint motion

- For extreme cases or as a last resort, surgical lengthening of the Achilles or of the gastrocnemius

To conclude, sometimes ankle equinus is considered a secondary finding in regards to certain foot problems we see in a chiropody setting when, as a matter of fact, it may be the underlying cause in more instances than we would think.

Mélanie Gagnon, B.Sc D.Ch

References :

Clifford, C. (2014). Understanding The Biomechanics Of Equinus. Podiatry Today,27(9). Retrieved August 11, 2019, from https://www.podiatrytoday.com/understanding-biomechanics-equinus.

Hill, R. (1995). Ankle equinus. Prevalence and linkage to common foot pathology. Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association,85(6), 295-300. doi:10.7547/87507315-85-6-295

Searle, A., Spink, M., Ho, A., & Chuter, V. (2017). Association between ankle equinus and plantar pressures in people with diabetes. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Biomechanics,43, 8-14. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2017.01.021